The Best Little Cinematographer in Texas: Celebrating Austin McKinney

Austin McKinney (far right) along with his life partner Lee Strosnider (far left)

The sultry landscape of Texas is not just famous for chainsaw massacres; indeed, actors such as Ethan Hawke, Owen Wilson, Jim Parsons, Eva Longoria, and Jennifer Love Hewitt are all major talents who were forged in the Lone Star State. Even Matthew McConaughey and Renee Zellweger were born in Texas, rather poetically making one of their earliest screen appearances in 1995’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation. It’s not just film actors either who emerge from Texas’ extraordinary crucible of talent, including filmmakers such as Stephen Carpenter (The Dorm That Dripped Blood), Frank Q. Dobbs (Enter the Devil), Stephen Herek (Critters), Fritz Kiersch (Children of the Corn), Richard Linklater (Waking Life), Robert Rodriguez (From Dusk Till Dawn), and of course, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre mastermind himself, Tobe Hooper. In the same era that Hooper’s swelteringly-terrifying shocker was being painstakingly filmed however, a little-known professional hailing from the same state was busy honing his own craft in the cinematography and camerawork landscape. He was soon to become a maestro of multiple filmic talents before unfortunately fading away into relative obscurity in his later life. That man was Austin McKinney.

There’s still a lot that remains a mystery about Austin, but we do know that he was born in Texas around the year 1929. His childhood was somewhat difficult, mainly because of the strained relationship he had with his father, who was reportedly hard on him. Austin was quite an animated child with lots of energy, but he also knew that he was somewhat different from others, something which may have contributed to his father’s treatment of him. As he entered adolescence and began to slowly mature into an adult, he started to foster an ever-growing appreciation for films and cinema, especially classic Hollywood pictures. He also began to become aware of his own burgeoning homosexuality, which caused some turmoil for the young man. He reportedly researched such topics by scouring through local libraries, where it was still treated as a mental disorder rather than the natural sexuality that it is understood as today. Apart from casting a pall over Austin’s cheery disposition, he also despaired that most medical journals and studies found that the ‘disease’ was incurable, causing him to weep profusely when he realised he would be this way for the rest of his life.

By the 1950s, Austin had already taken his first step in the world of film, studying and eventually graduating from the Theatre Arts program at the University of California in Los Angeles. It’s here where he learned the essentials of film-making and began to cultivate his precise work ethic and sense of filmic style. One of his earliest documented works was in 1951, a short entitled Toast to Our Brother directed by fellow student Tom Graeff and documenting the flourishing student life at UCLA. His ingenuity also allowed him to work around the shortcomings of contemporaneous cameras that lacked the ability to shoot sound, inventing a small audio device that could replay recorded dialogue so that actors could appropriately lip sync to dialogue that would be properly captured later. Director Tom Graeff was impressed so much that the device was retained for use on a further three films of his. Austin also met with probably the most important figure in his life, a young man called Lee Strosnider who specialised in sound mixing. The pair bonded over their mutual love for film and decided to live together shortly before college ended. After his first few pictures in California with Graeff, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia in order to work for a production company that made industrial films, working in various roles. His cult film success wouldn’t begin however until the dawn of the new decade, one of social revolution, counterculture, and the relaxation of taboos: the 1960s.

Austin’s first major gig came in the form of infamous B-movie, The Beast of Yucca Flats, directed by Coleman Francis. Austin not only did the cinematography, editing, and assisted Francis in direction, but he got to work with his roommate Lee Strosnider, who also assisted with cinematography and editing on Francis’ flick. While it’s not known nowadays for its high quality, mainly regarded as a Plan 9 From Outer Space-esque curio piece, it did help Austin forge some early connections that would benefit him later in life. He went on to edit Ray Dennis Steckler’s exploitation film The Thrill Killers in 1964 where he first met actor Gary Kent, and then became a production manager on Steckler’s next film, 1964’s The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies!!? Lee Strosnider also worked on these films alongside McKinney as the sound mixer, the two becoming ever closer with each other.

Austin then became acquainted with director Jack Hill, acclaimed today for his work on 1967’s Spider Baby and the blaxploitation genre with Coffy, The Big Doll House, and Foxy Brown. He worked on Hill’s own racing-themed thrill ride Pit Stop in 1967 (which Strosnider produced) and due to proving himself more than capable, he was able to assist Hill with his next project. Hill was required to shoot scenes with Boris Karloff in the United States, with the footage to be integrated into a small selection of low-budget horror films primarily filmed and directed in Mexico by Juan Ibáñez. The four films were House of Evil, Fear Chamber, Isle of the Snake People, and The Incredible Invasion, all of which were shot in the last few years of the ‘60s and released years after Karloff’s death in the early ‘70s. Now comfortable with his own identity due to his burgeoning relationship with Strosnider and having gained more on-set experience, Austin began to behave much more authentically himself, which in his case was more flamboyant and animated when he became passionate or involved on the job. This oftentimes dramatic personality would cause tension with other crew members, supposedly causing a disagreement between McKinney and Hill that resulted in Hill quietly refusing to work with him on future projects.

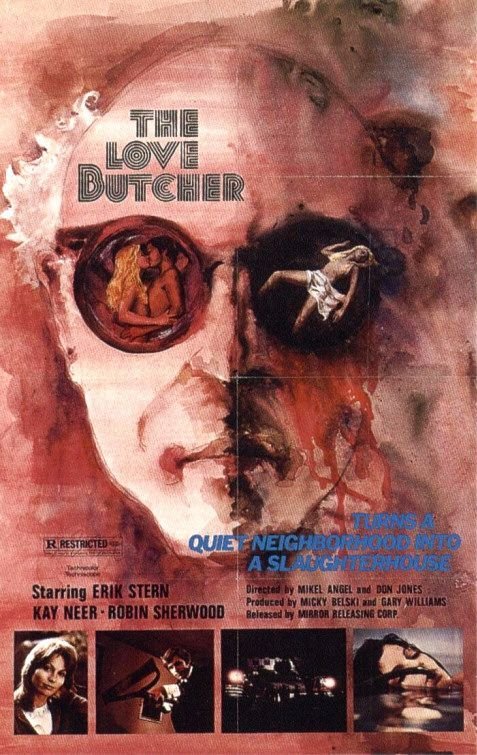

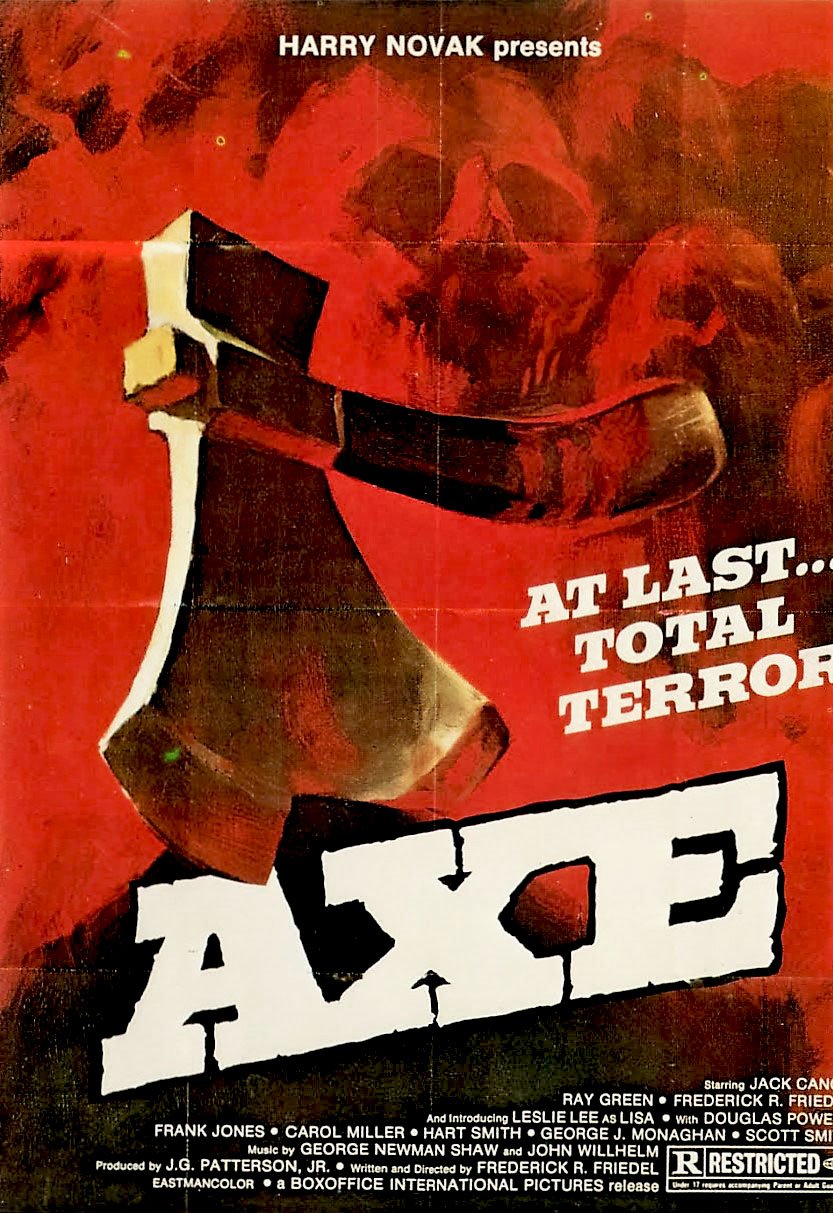

As the mid-70s approached, Austin travelled to North Carolina to work on the cinematography for a production helmed by photographer-turned-filmmaker Frederick R. Friedel. This turned out to be Friedel’s debut feature Lisa, Lisa, released internationally as Axe. On the set, Austin became firm friends with the crew, including director Frederick ‘Rick’ Friedel, production manager Phil Smoot, and make-up artist Worth Keeter. Smoot still has countless fond memories of Austin and his eccentric behaviour, reminiscing about when Austin would react overdramatically if Phil would spot a cute girl walking past or talk about women, trying to centre attention on himself instead. Smoot has only realised in retrospect that this was due to Austin having a crush on him; Smoot himself would only become aware of Austin’s sexuality around 1980 after he had an extended visit to Austin’s home. The camaraderie the crew had on Axe was such a pleasant experience that Austin was happy to return as a cinematographer on Friedel’s subsequent picture, 1976’s Date with a Kidnapper, often released as Kidnapped Coed. This second film also had Don Jones involved in the sound department, who had a good relationship with Gary Kent whom he worked on the controversially titled Schoolgirls in Chains (released in the UK as Abducted). Due to this connection, Austin was brought on board by Jones to work on Mikel Angel’s The Gardener, which Jones had acted as cinematographer himself. The tame initial cut was rejected by the producers and Angel left the production as a result, forcing Jones to take the director’s seat with Austin taking over on the cinematography; it was eventually made more graphically explicit and released as The Love Butcher. At around the same time, Austin worked in his usual capacity on the fairly unique blaxploitation flick Redneck Miller in 1976.

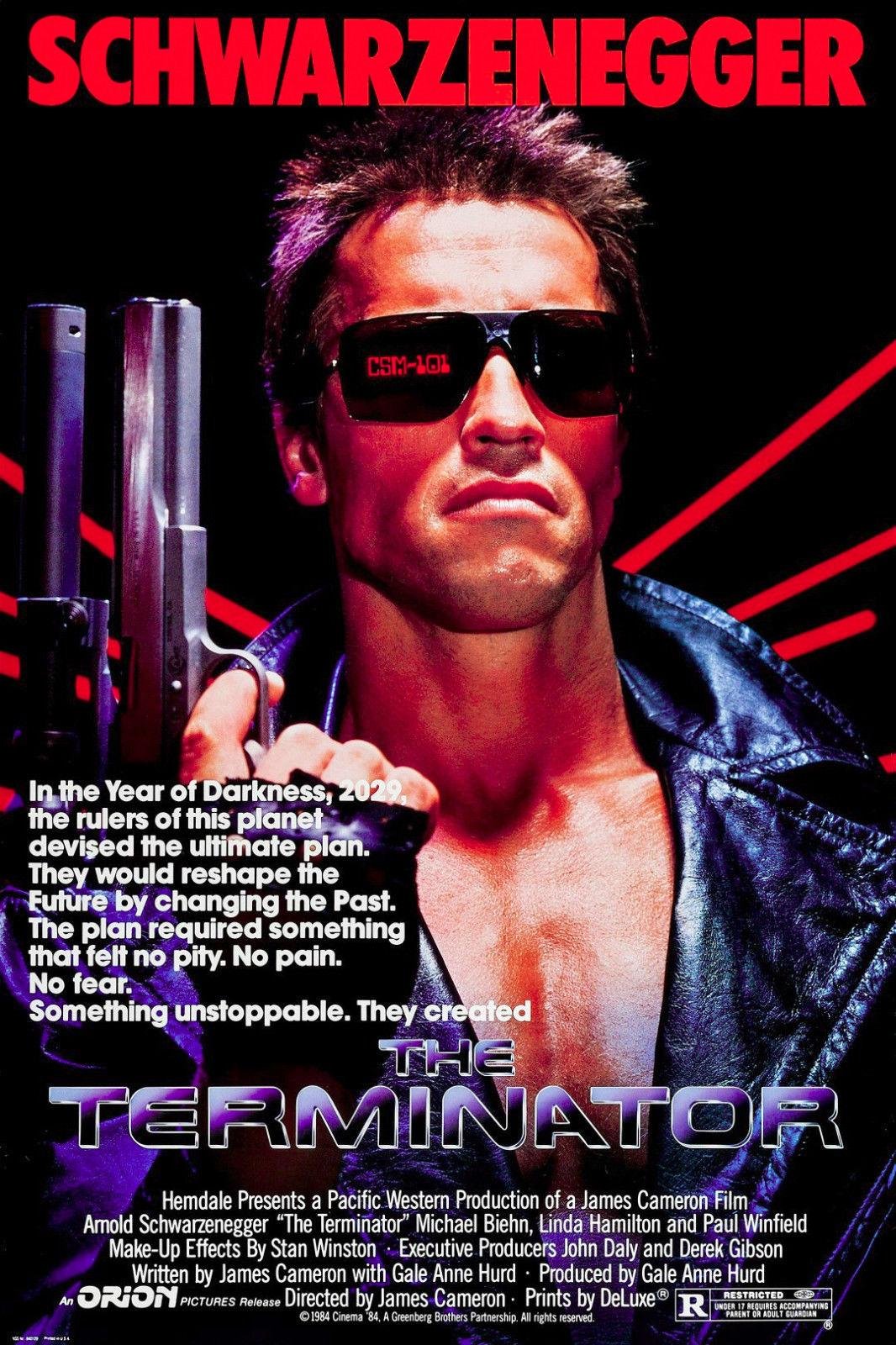

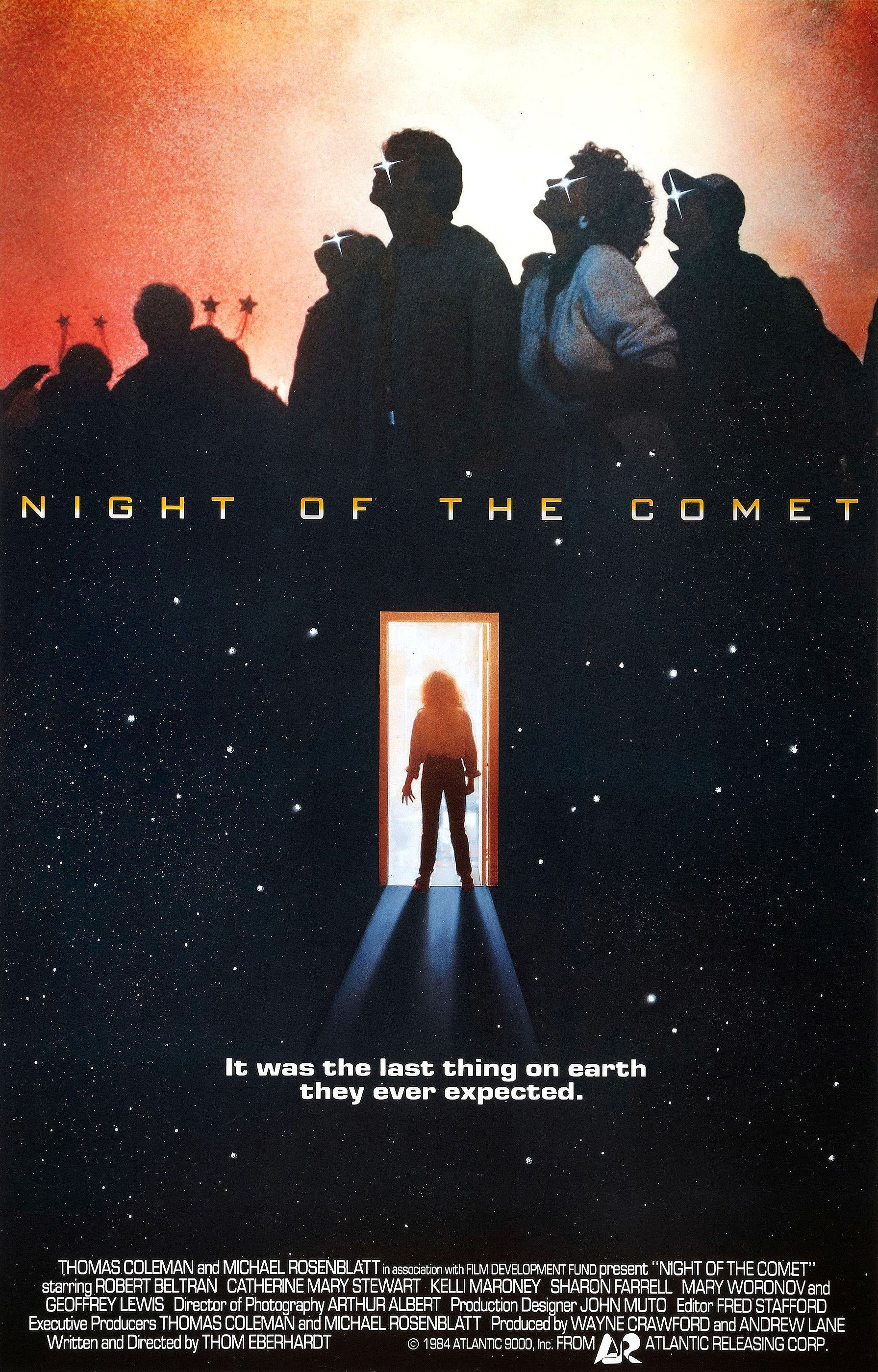

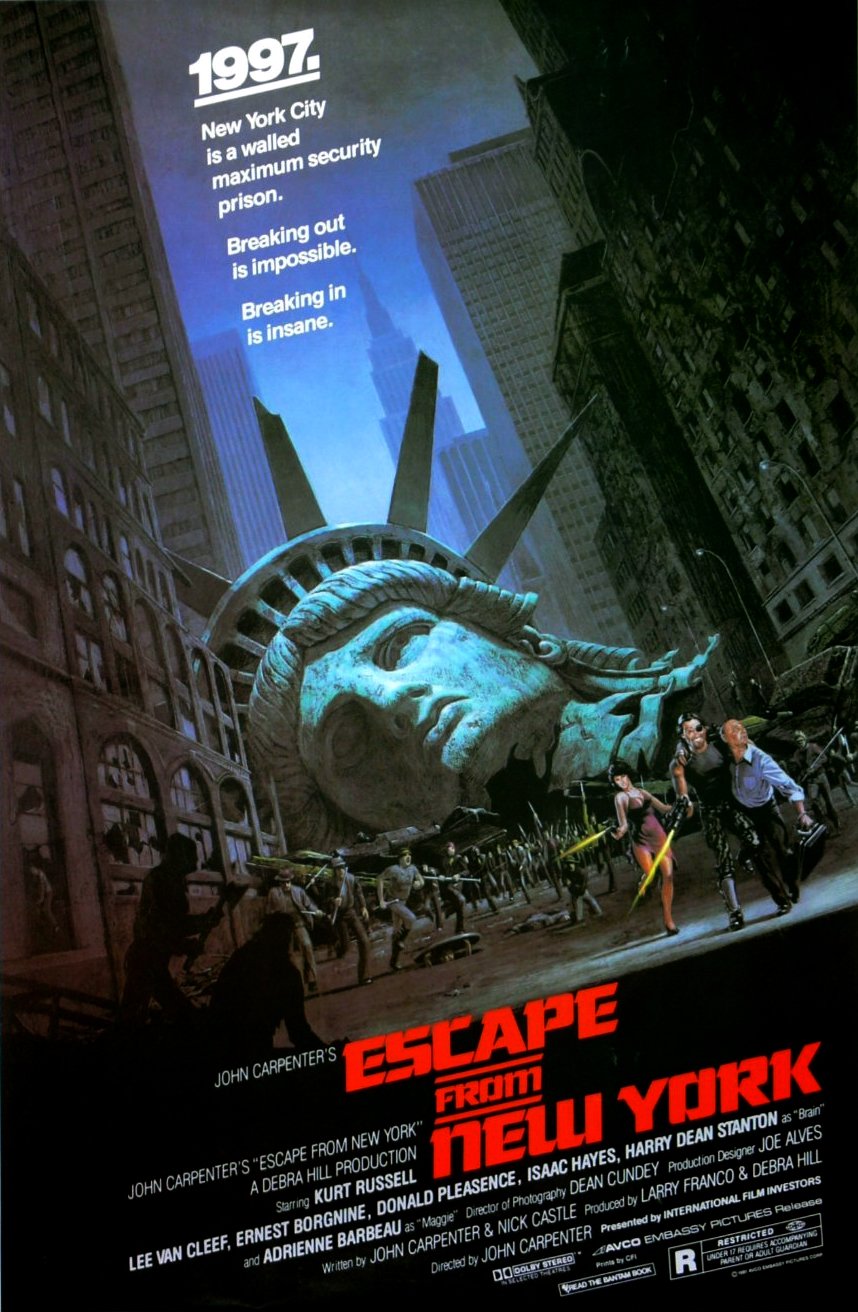

By the turn of 1980, shortly after Strosnider had completed sound work on John Carpenter’s Halloween and various TV projects, both Austin and Lee were in love exclusively and had already lived together for most of their professional career, both continuing to have major roles in the film-making world. Lee continued as a stalwart sound mixer on TV movies like Fallen Angel and Fly Away Home, before delving into low-budget cult favourites like 1984’s Fleshburn, 1985’s Ghoulies and Runaway Train, the TV series Freddy’s Nightmares, and Steve Miner’s Warlock in 1989. Austin discovered his own love and talent for visual effects, providing them for 1980’s Battle Beyond the Stars (where he met a young James Cameron), Roger Corman’s Galaxy of Terror (which he also did the cinematography for), John Carpenter’s Escape From New York, 1982’s Sorceress, summer blockbuster Jaws 3D, the post-apocalyptic Night of the Comet, James Cameron’s The Terminator, and 1987’s Warlords From Hell. He and Lee reunited on 1988’s Invasion Earth: The Aliens Are Here, and 1989’s A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child, where Austin assisted Lee directly in the sound department as a boom operator. By the time of the 1990s, both Austin and Lee felt sufficiently comfortable to speak openly about the nature of their relationship. Unfortunately, this coincided with the general decline of their involvement with the film industry, with Lee’s final credit being on a documentary entitled The First 100 Years: A Celebration of American Movies in 1995. Austin continued to provide some visual effects for the likes of 1991’s Beastmaster 2, and provided sound mixing for 1991’s Molly and the Ghost, 1992’s sequel Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, and 1997’s Last Lives. His final credit would be on William Olsen’s 1997 film Southern Belles, at the age of 68.

Decided to live out the rest of their days in each other’s company, Austin and Lee lived peacefully for the next ten years outside of the limelight. The next time he was noticed publicly was in 2007, when cult director Quentin Tarantino produced a print of Redneck Miller for exhibition at the Grindhouse Film Festival, which Austin and Lee attended. Sadly however, he suffered an intense stroke just a few weeks afterwards, affecting his ability to communicate properly and impacting on his health permanently. He nonetheless refused to just sit and demonstrated his signature energy and excitement, continuing to attend screenings at various film festivals, forging a strong friendship with American filmmaker Elle Schneider, and even visiting his old friend James Cameron on the set of Avatar, then still in production. By 2011, Austin’s ill health had required him to be housed in a care home as he had developed a degenerative disease as well, often unable to use the correct words when speaking. Still, he fought to the bitter end and still attended film screenings, eager to chat animatedly about his career and relive his rich history in the film-making world.

In November of 2013, the inevitable but incredibly heartbreaking news had dawned: Austin had passed away at the age of 84. The equally elderly Lee Strosnider was inconsolable at the loss of his life partner of over 60 years, faced with the prospect of carrying on without the companionship of the man he loved. Only a mere 10 days later, Lee suffered a fatal stroke and passed away as well, seemingly unable or unwilling to live without his soulmate. Despite a long-term dedication to the movie business and his involvement with countless films considered today to be classic or cult in nature, Austin McKinney never really got the recognition he deserved. He was quietly cremated after his death and a memorial dedicated to his memory has so far not materialised in either his Los Angeles home or his home state of Texas. Austin’s filmography and life story would have entirely passed me by if I hadn’t been studying the British phenomenon of video nasties, which includes many of the films in and around the time he was active. Frederick Friedel’s Axe and Don Jones’ The Love Butcher are two which Austin worked on directly, while Jones’ Schoolgirls in Chains and Jack Hill’s Foxy Brown also ended up on the now infamous lists. The works of his Texan contemporaries also play a part in the video nasty furore, namely Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Stephen Carpenter’s The Dorm That Dripped Blood (under the title Pranks), and Frank Q. Dobbs’ Enter the Devil. But should Austin’s legacy really just be a footnote in another country’s socio-political scandals? “No way,” is the answer.

This Pride month, I’m proud to talk about and celebrate the life and work of Austin McKinney. His artistic sensibility, eccentric personality, and loving soul will be forever memorialised in the generous works he’s provided to us over the years. He deserves to be remembered for the care and attention he gave to both his work and his filmmaking colleagues. The love that he shared with his soulmate and fellow professional Lee Strosnider should be screamed from the rooftops in admiration and jubilance. A little-known member of the LGBTQIA+ community who never quite got his contribution and his influence acknowledged by future generations.

Let’s change that.

Special thanks to Phil Smoot and Elle Schneider for their invaluable willingness to talk about Austin’s life.