Unlucky for Some: The Crystal Lake Video Nasties

It’s that time of year again, where knightly orders are arrested and tortured for charges of heresy, where brokers stir up stock market crashes, where royal residences get bombed in wartime, where rugby teams crash into the Andes… and where a certain killer rises from Crystal Lake’s depths to terrorise new teenage victims. Yes, it’s Friday the 13th again, often considered one of the unluckiest days in Western superstition for a multitude of cultural and social reasons. While some other countries have differing variations on the doomed date, it’s generally accepted that a Friday the 13th is a date to be cautious of.

Back in the early 1980s when the seeds of the hit slasher franchise were about to germinate in the fertile soil of the Golden Age, the United Kingdom was undergoing the early stages of its own cultural metamorphosis. Due to a confluence of political strife, mass unemployment, social cuts, and a war over the Falklands, Great Britain was ironically not doing that ‘great’. As is the case with most democracies even today, the government in power needed a new distraction for the masses, a new scapegoat to direct the people’s anger towards, and a new crusade to ponder and debate endlessly in the mostly symbolic chambers of Parliament. It just so happened that at that time, VHS was rapidly emerging as the country’s entertainment medium of choice. Cinema attendance was in decline, with most families and younger generations preferring to enjoy home comforts, allowing the sales of video recorders to skyrocket and video rental business to spike in an unprecedented swell. This growth was so quick that the market had little time to implement either quality control or a classification system that was in use at theatres. This short-lived period of video availability would soon come under fire by conservatives from all avenues of British society, who gushed forth with their ‘concerns’ that the nation’s children were devouring a whole smorgasbord of violent filth, obscene sex, and gory excesses, in effect grooming them into an inescapable lifestyle of vice, crime, and antisocial rebellion. Therefore, the witch-hunt began.

As the media panic settled in, nightmare stories by national newspapers began hyperbolising all of the country’s ills as a means to attack anyone who defended the idea of the so-called ‘video nasties’, disreputable and unjustifiable films on video that were certain to affect anyone who watched them in negative fashion. The Obscene Publications Branch soon weighed in on the argument, proving via several test cases with the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) that non-pornographic films could fall afoul of the Obscene Publications Act, a law usually reserved for then-illegal pornographic works. The DPP wasted no time and secretly issued a list of movies that he felt would be successfully prosecuted under that law, immediately instructing police forces to raid dealers and distributors for the offending films. The original list contained 72 films, including flicks like The Beyond, Evil Dead, Last House on the Left, I Spit on Your Grave, Driller Killer, and SS Experiment Camp, mostly consisting of imports from either the US or Europe. Whilst some of these titles like The Boogeyman and Dead & Buried were ultimately dropped from the list after several acquittals in court, others like Faces of Death and Nightmares in a Damaged Brain were vilified by judges and juries, earning the individual on trial a prison sentence or a hefty fine for being involved in the film’s distribution or rental. In addition, a supplementary list was also supplied to police known as the Section 3 list, a reference to an alternative part of the Obscene Publications Act that allowed legal obscenity to be admitted through the action of forfeiting the goods. In a stroke of luck however, by forfeiting the goods, potential offenders escaped any legal reprisals and wouldn’t have to appear in court, leading most dealers to just comply with the confiscations in order to escape any prosecution. On this secondary list were such films as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The Thing, Happy Birthday to Me, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, and of course the grand-daddies of them all: Friday the 13th and Friday the 13th Part 2.

It’s a challenge to try and encapsulate the full extent of the cultural impact of the first Friday the 13th film, mainly because its reach is immeasurably far and wide. After the release of John Carpenter’s Halloween, horror audiences were provided with a new type of cinematic snack to whet their appetites with, an easy-to-follow template of a cast of victims who would be systematically stalked and killed before a final confrontation between the assailant and the last surviving girl. Thus, the slasher film was born. Upon the success of Carpenter’s masterpiece, several other projects immediately went into production with similar premises, slowly building to a saturation point which was catapulted into popularity by the summertime release of Friday the 13th, notably distributed by Paramount Pictures, the first such high-profile motion picture studio to acquire a low-budget slasher film. The reaction to the film’s release was phenomenal, grossing a staggering $59.8 million in worldwide box office sales, against a comparatively meagre budget of $550,000, driven mostly by swathes of younger viewers attracted by the marketing campaigns. Directed by Sean S. Cunningham and scripted by Victor Miller, the film is set within a summer camp in the small town of Crystal Lake, named after its eponymous body of water. During the 50s, two teenagers are killed by an unknown killer, who seemingly goes on to start fires and pollute the waters in subsequent years in a feverish effort to keep Camp Crystal Lake closed. When entrepreneur Steve Christy obtains the property and enlists the help of a group of teenage counsellors to get the place ready for the new season, the killer emerges once more from the shadows, stalking and killing the hapless kids in a round-robin of violent murder. With only the naive Alice left standing, she is seemingly saved by the kindly Mrs. Voorhees who used to work at the camp as kitchen staff. To Alice’s horror however, Mrs. Voorhees is in fact the killer, driven mad by the death of her son Jason who drowned in Crystal Lake in the 1950s, unseen by the camp counsellors who were busy having sex. Determined to not allow the same situation to occur again, she has killed Alice’s friends to ensure the camp doesn’t open and now turns her attention to Alice herself. After a gruelling cat and mouse game between the pair, Alice manages to seize the lunatic’s machete and brutally decapitates her in a frenzied panic. Exhausted, she drifts away in a canoe, only to be violently seized in the morning sun by a rotten Jason, who bursts from the lake’s waters to drag her under. Waking in the hospital hours later, she insists she saw the boy to a skeptical police officer…

A sequel was greenlit almost immediately upon the success of the original, with director Steve Miner at the helm, furnished with a dramatically increased budget of $1.25 million. Though it seems a little clunky by today’s standards, the sequel diverted somewhat from the established canon of the first movie to bring back the Jason character, arguably enshrining the series in horror fandom forever as it developed over time. Alice is recovering from her ordeal at the hands of Mrs Voorhees by staying in Crystal Lake alone, only for an intruder to break into her home and kill her. Several years later, a new group of counsellors head to the area near Camp Crystal Lake to undergo a course at a counsellor training centre, aware of the location’s notoriety and bloodied past. It soon becomes horribly apparent that the intruder who killed Alice is living in the woods, slaying the unaware counsellors-in-training for daring to venture in his territory. Assistant team leader Ginny has a strong feeling as to the identity of the maniac, and after narrowly avoiding his attempts to kill her, she stumbles upon his remote shack in the dense woodlands, finding the head of Mrs Voorhees enshrined upon her filthy sweater, surrounded by candles and the strewn bodies of victims. Correctly guessing that the assailant is Jason Voorhees himself, having survived his childhood drowning, Ginny tricks her attacker by donning the sweater and speaking to him as Mrs. Voorhees. The ploy initially works before Jason catches on, leading to a struggle between Jason, Ginny, and Paul until Ginny seizes the upper hand and plunges a machete through the killer’s shoulder, seemingly killing him. As the pair rest and recover from their ordeal, Jason suddenly bursts through the windows of the cabin, wrenching Ginny from safety. She faints, only to wake up the next morning unscathed, with no clue as to the whereabouts of Paul…

It’s no secret that the early successes of the Friday the 13th series posed significant problems for Paramount Pictures, mainly due to its long-standing reputation in the US as a prestigious company with little controversy. With critics coming down hard on Friday the 13th’s graphic scenes of sex and violence, Paramount was reluctant to let further projects be so unfettered as to ruin their position as a paragon of filmed entertainment. The first film suffered cuts by the MPAA on its original theatrical run, losing gory details from the throat-slashing of Annie, Jack’s arrow through the neck, Marcie’s axe in the head, and the finale in which Mrs. Voorhees is beheaded by Alice. Even with these moments of censorship, the critics were still unhappy, leading to a slew of criticism from audiences and professionals alike, condemning the film for showing such graphic content. Friday the 13th Part 2 fared even worse, with Alice’s icepick demise, Crazy Ralph’s garrotting, the sheriff’s hammerblow to the head, Scott’s throat-cutting, Mark’s machete in the face, and Jeff/Sandra’s spear impalement reduced heavily to remove most of the gore, reducing the film to a fairly bloodless experience. In an even more tragic turn of events, the footage deleted was actually destroyed afterwards too, making a definitive uncut version impossible to release. The aforementioned scenes were however miraculously found on a VHS copy belonging to a crew member only a few years back, only surviving today as part of Scream Factory’s Complete Collection box set. Subsequent entries in the Friday the 13th series also ended up being subject to the same censorious approach from the MPAA, with only 1993’s Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday and 2001’s Jason X released without any interference from the censors. Arguably however, the UK authorities took an even more extreme approach to the controversy of Crystal Lake slayings.

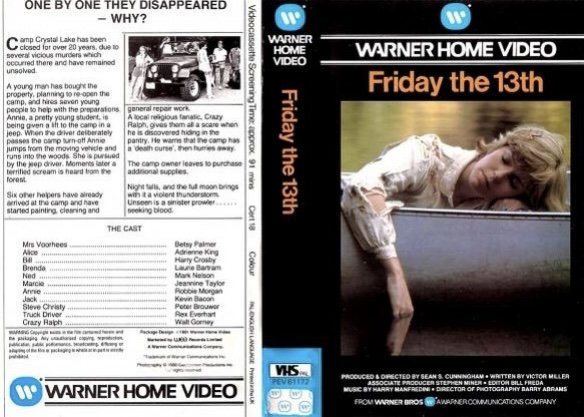

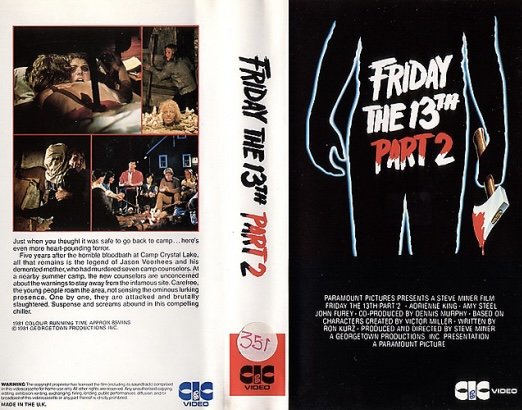

While Paramount Pictures were responsible for domestic distribution, Warner Brothers secured the rights for foreign distribution of Friday the 13th, leading to a fairly rare event in the UK where the unrated version was submitted for exhibition. The BBFC (then the British Board of Film Censors) passed the film without any additional cuts, leading to the uncut edit of Cunningham’s film being Britain’s standard version. The film ran its course in cinemas without too much issue, adding to the film’s already high box office earnings, before Warner decided to release the film on VHS as well in 1982. The same unrated print ended up on the video market just as the video nasty scare was beginning to bubble more intensely under the surface of society. For Friday the 13th Part 2, the MPAA’s butchered print was the only option available as an unrated version wasn’t compiled, so this print was passed without further tinkering by the BBFC and equally had a fairly uncontroversial theatrical run. The same version was then released by CIC on home video in 1983. When the dreaded DPP lists were issued to the police, both Friday the 13th and Friday the 13th Part 2 found themselves listed, now liable for seizure under Section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act. In response, Warner immediately superseded its current run of tapes with an updated VHS in 1983 that instead featured the R-rated print, missing the more extreme moments of bloodshed, though there’s very little evidence that this ultimately stopped the film being seized. Unlike the titles seized under Section 2, films confiscated under Section 3 charges were immediately sent away for incineration and destruction under the watchful eye of the Obscene Publications Branch in Scotland Yard.

As is the case for many of the video nasties, it’s quite difficult to define exactly why the first two films of the Friday the 13th series were considered obscene by the Director of Public Prosecutions. Both films played in UK cinemas without any additional cuts from the BBFC, with the first film actually playing in its uncut format as well, notably without any loud opposition to their lurid content. With The Burning and Blood Bath (Twitch of the Death Nerve) both being singled out for prosecution, it’s possible that the association with summer camp or lakeside slashers was what initially brought attention to the film, as well as the fact that it was one of the original slasher films to set off the initial explosion in popularity. The genre itself may have been the entire reason, as slashers were common sights on the video nasties lists, with examples like Graduation Day, Home Sweet Home, Madhouse, Bloody Moon, Unhinged, Rosemary’s Killer (The Prowler), Honeymoon Horror and Pranks (The Dorm That Dripped Blood) all occupying the same shelves as the Crystal Lake chillers. There were also a lot of ‘guilt by association’ inclusions on the list too, such as Cannibal Holocaust causing any other films with ‘Cannibal’ in the title to be seized, or the notoriety of Driller Killer leading to tool-related splatter like The Toolbox Murders and Texas Chain Saw Massacre to be equally condemned. To that end, high-profile horror movies like The Evil Dead, The Thing, Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and Night of the Living Dead were already setting a precedent that audience reception or positive critical responses were not a shield to obscenity charges, so the Friday movies may have been sufficiently well-known to authorities due to their less-than-warm analysis by American media. A moment where one of the counsellors decapitates a snake for real may have also contributed to the decision, since unsimulated animal slaughter is mostly illegal under UK law and other nasties like Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll, Tomb of the Living Dead (Mad Doctor of Blood Island) and most of the cannibal cycle movies had already ratcheted up the DPP’s sensitivity to this issue. The graphic beheading of Mrs. Voorhees may also be a point of contention, since similar sequences in Bloody Moon, Absurd, The Slayer, and Island of Death likewise came under fire for depicting gratuitous explicitness. The authorities at the time were also concerned about the conflation of violence with sexual activity, so the scenes of Marcie and Jack having sex while the corpse of Ned lies above them, as well as the scene of Jeff and Sandra being penetrated with a spear post-coitus were both likely viewed with the same ‘concerns’. Part 2 is a particularly baffling inclusion since the R-rated cut exhibited by CIC on video has already been extensively censored. In an equally befuddling way however, it may be simply because the opening of Part 2 reuses a good portion of the original’s closing sequences; Ulli Lommel’s The Bogey Man (The Boogeyman) was listed as a nasty, with its sequel Revenge of the Bogey Man (Boogeyman 2) being hauled in by proxy due to Lommel’s experimental approach in reusing a significant amount of the original film’s footage. Since the DPP found The Bogey Man’s violent sequences to be problematic, their inclusion in Revenge of the Bogey Man would mean that title had to be added for completeness. Friday the 13th Part 2 may just be a victim of this defective approach after all, with the original film taking the majority of the flak.

Regardless of the reasons, Friday the 13th and Friday the 13th Part 2 are quite unique additions to the video nasty checklist, mainly because they would have ascended into pop culture stardom irrespective of their legal troubles in the UK, something that they would share with only a handful of other nasties. They are also some of the most financially successful movies to be labelled as nasties, as well as some of the earliest to be re-released after the panic was over; Part 2 was reissued without any cuts as early as 1987, whilst the original was also released in ‘87 though it was the safer R-rated cut - the unrated version wasn’t passed uncut in the UK again until 2003.

As cineliteracy has improved and public experience has matured over the years, these films are now as uncontroversial as using bricks to make houses. Ardent fans of these movies can now enjoy them freely and without judgement, in beautifully remastered versions packed with thoughtful extras and bonuses. The next time you place your DVD or Blu-Ray copy into your machine, take a brief moment to think about all those years ago, when it was actually against the law to sell or rent this film in the UK… how times do change!

Read the original posting here at Daily Grindhouse